Experiments are a powerful tool for investigating causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, researchers manipulate one or more independent variables and measure the effect of this manipulation on one or more dependent variables. By carefully controlling the experimental conditions and minimizing the influence of extraneous variables, researchers can draw valid conclusions about the causal relationships between variables.

Designing a good experiment requires a systematic approach and a thorough understanding of the system being studied.

There are five key steps in the experimental design process:

- Define your variables

- Write your hypothesis

- Design your experimental treatments

- Assign your subjects to treatment and control groups

- Measure your dependent variable

Step 1: Define your variables

The first step in designing an experiment is to clearly define your variables. This involves identifying the independent variable (the variable you manipulate) and the dependent variable (the variable you measure) in a specific research question. You should also consider any extraneous variables that could influence your results and plan how to control for them.

- Example question 1: Does the amount of fertilizer affect the growth rate of plants?

- Example question 2: Does the type of music played in a store affect the amount of time customers spend shopping?

To transform your research question into a testable hypothesis, you must first identify the key variables and then formulate predictions about their relationship. Begin by clearly stating the independent and dependent variables in your research question.

| Research question | Independent variable | Dependent variable |

| Does the amount of fertilizer affect the growth rate of plants? | Amount of fertilizer | Growth rate of plants |

| Does the type of music played in a store affect the amount of time customers spend shopping? | Type of music played in the store | Amount of time customers spend shopping |

Next, consider potential extraneous and confounding variables that could influence the results of your experiment. Develop strategies to control these variables and minimize their impact on your study.

| Research question | Extraneous variable | How to control |

| Does the amount of fertilizer affect the growth rate of plants? | Soil quality can vary and influence plant growth independently of fertilizer amount. | Control experimentally: use the same type of soil for all plants in the experiment. |

| Does the type of music played in a store affect the amount of time customers spend shopping? | Time of day can affect shopping behavior, as customers may spend more or less time depending on the hour. | Control experimentally: conduct the experiment during the same time period each day to minimize time-of-day effects. |

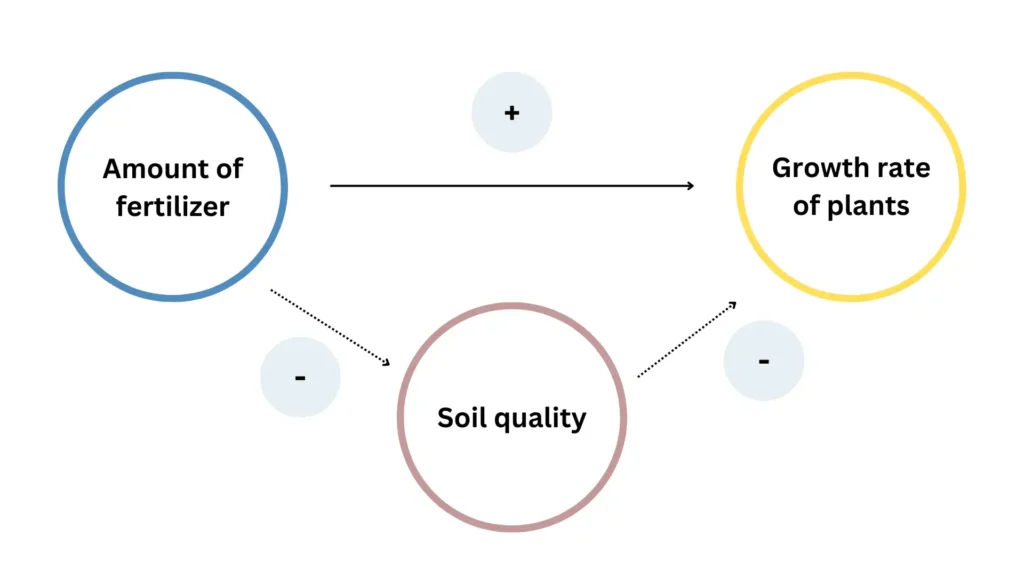

Lastly, you can create a visual representation of the variables and their relationships by constructing a diagram. Utilize arrows to illustrate the potential connections between variables, and incorporate positive or negative signs to indicate the predicted direction of each relationship.

Here we predict that increasing the amount of fertilizer will increase the growth rate of plants, while factors such as soil quality, watering frequency, and light exposure may also influence plant growth independently or by interacting with the effects of fertilizer.

Step 2: Write your hypothesis

Once you have defined your variables, you can write your hypothesis. A hypothesis is a testable prediction about the relationship between your independent and dependent variables. It should be specific, measurable, and falsifiable.

| Null hypothesis (H0) | Alternate hypothesis (H1) |

| The amount of fertilizer has no effect on the growth rate of plants. | The amount of fertilizer affects the growth rate of plants. |

How do you design a controlled experiment?

- Systematically and accurately manipulate the independent variable(s).

- Precisely measure the dependent variable(s).

- Control any potential confounding variables that may influence the results.

The way you manipulate the independent variable can impact the experiment’s external validity, which refers to the extent to which the results can be generalized and applied to real-world situations.

First, you need to decide how widely to vary your independent variable.

In the context of the fertilizer and plant growth experiment, you can choose to vary the amount of fertilizer:

- Within the recommended range for the specific type of plant you are studying.

- Over a wider range to observe the effects of under- and over-fertilization on plant growth.

- Over an extreme range that goes beyond the recommended amounts to test the limits of plant tolerance to fertilizer.

Second, you need to choose how finely to vary your independent variable. Sometimes the nature of your experimental system dictates this choice, but often you will need to make a decision, which will impact the level of detail you can infer from your results.

In the fertilizer and plant growth experiment, you can choose to treat the amount of fertilizer as:

- A categorical variable: either as binary (with fertilizer/without fertilizer) or as levels of a factor (no fertilizer, low fertilizer, medium fertilizer, high fertilizer).

- A continuous variable (measuring the precise amount of fertilizer applied to each plant in grams).

Step 4: Assign your subjects to treatment groups

Once you have designed your experimental treatments, you need to assign your subjects to treatment groups. This involves deciding on the study size and randomly assigning subjects to groups. You should also include a control group, which receives no treatment.

Choices you need to make include:

- A completely randomized design vs a randomized block design.

- A between-subjects design vs a within-subjects design.

A completely randomized design vs a randomized block design

| Completely randomized design | Randomized block design |

| All subjects are randomly assigned to treatment groups, regardless of their characteristics. | Subjects are first divided into blocks based on a characteristic that might influence the results (e.g., plant species), then randomly assigned to treatment groups within each block. |

When randomization is impractical or unethical, researchers may employ partially-random or non-random designs, known as quasi-experimental designs, in which treatments are not randomly assigned to subjects.

A between-subjects design vs a within-subjects design

| Between-subjects (independent measures) design | Within-subjects (repeated measures) design |

| Each subject is assigned to only one treatment group. | Each subject receives all treatments, in a random order. |

In a within-subjects or repeated measures design, individual responses are measured over time to capture an effect as it emerges. Counterbalancing techniques, such as randomizing or reversing the treatment order, are also employed to minimize the influence of treatment order on the results.

Step 5: Measure your dependent variable

The final step in designing an experiment is to plan how you will measure your dependent variable. This involves choosing a reliable and valid measurement method and deciding on the timing and frequency of measurements.

Example: In the plant growth experiment, you might measure plant height every week for six weeks using a ruler. This provides a quantitative measure of plant growth rate over time.